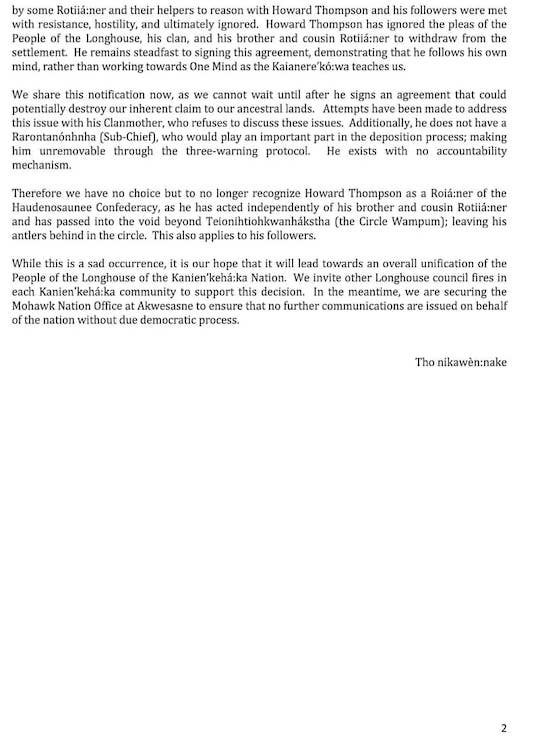

MNN. Dec. 7, 2024. The ‘salad bowl effect’ is to bring all kinds of people to onowarekeh turtle island with different mindsets and ways and putting them into a “mixing bowl” with all their clashing ideologies. In order to populate turtle island, the perpetrators emptied prisons, insane asylums, poor houses, orphanages, gathered prostitutes, debtors, mail order brides now called white collar workers, and anyone they wanted to get rid of. The resulting population of out-of-place people is lost imported people who don’t belong here in the land of peace. Many even call themselves “Heinz 57 Variety”. It is a sordid history. They are all descendants and beneficiaries of the atrocities started by the Vatican. To stay these people agreed to follow the kaianerekowa great peace. As most now know they broke all the agreements made with us.

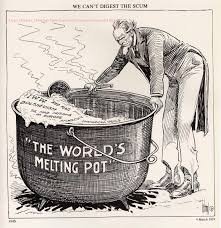

Canada and the Pope have admitted the role of church and state in committing genocide on the original people of turtle island because of their indigenous group membership, race, ethnicity, religion, language and their desire to own beautiful onowarekeh turtle island. Politicide is murder of any person by a government for a political purpose. Mass murder is the indiscriminate and targeted killing of any person or people by a government or institution. This is how war is created by these intruder governments for power, greed and corruption. They came here to take over. Their plan was to surround the natural people, destroy nature and all life on our land to annihilate and take over all of turtle island. They poisoned our water, animals, people and all our natural world so they could build their artificial system and commercial empire to benefit themselves.

One time we had all the necessities of life. The kaianerekowa great peace tells us that we do not fight until we die. We must fight until we win! The invaders continue their genocide plan. Our lives were made miserable so as to make us want to die. Today many of us feel more alone among whites than if we had been left on our land to care for our people and our mother earth. Everything we do is twisted to mean something else and then penalized us for thinking otherwise. Our voices are not heard. What is said about us is false.

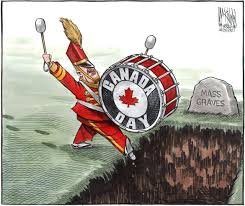

These intruders brought some very bad spirits with them to our land. They forced us to live on small plots of land, hardly enough space for us to live the way creation intended with less animals to feed us, toxic water to make us sick and kill us and hardly enough trees to heat our homes.

These intruders brought some very bad spirits with them to our land. They forced us to live on small plots of land, hardly enough space for us to live the way creation intended with less animals to feed us, toxic water to make us sick and kill us and hardly enough trees to heat our homes.

We try to understand the intruders. Many people like to watch tv shows about serial killers. Maybe these could provide us some clues. The serial killers enjoy what they do or they wouldn’t do it. They have no regrets about it and spend their time covering up their crimes. The police have a hard time catching these serial killers, so we’re lead to believe. In our situation where the church and state admit the mass murders by the intruders, few have been charged for these crimes because their institutions made cover-up laws allowing them to murder or disappear us until eventually there would be none of us left. The killers made plans on how to cover up what they did to us. It seems to be a game between the killers and the police who pretend they are looking for them but rarely find them. They called us “savages” which is the beginning of fake news and misinformation. This is one way Canada empowers themselves in a sick way. They don’t understand why we cannot reconcile with serial killers.

These shows are popular because the benefitters of the genocide are learning how to get away with it. They don’t feel guilty, only fear getting caught. The serial killers get ideas on how to do it again with better ways on getting away with it.

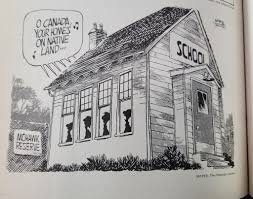

Such killings could be a mental illlness or a symptom of psychopathy. It certainly isn’t natural to us. To them it is a necessity and they set up institutions and people to run the annihilation and theft program with impunity. They lack remorse and guilt otherwise they would not do it on such a grand scale. Criminologists and policing authorities surmise it could be impulsiveness and difficulty in controlling something so random. It could be predatory behaviour on the part of a few where, in our case, the intruders searched out and studied us and then wrote out an extensive plan of action to murder us out of existence. The intruders have no empathy for us for murdering our children and babies from which they are benefitting. They are unconcerned that they kidnapped our children and sent them to state and church run slaughterhouses known as ‘Indian Residential Schools’.

The intruders keep bringing people over here to run their abattoir system. The intruders’ laws continue to allow them to kill us, to hide us, to build on top of our bodies in order to steal our land and carry on the degradation of our mother earth. They have a severe thirst for violence.

The intruders keep bringing people over here to run their abattoir system. The intruders’ laws continue to allow them to kill us, to hide us, to build on top of our bodies in order to steal our land and carry on the degradation of our mother earth. They have a severe thirst for violence.

In the United States 82% of serial killers are of the white race [99% are males], known as “hunters of humans”, 15% are black and 2.5% are Hispanic. The US has the most serial killers, the total surpassing the next ten countries combined. Canada is in the top 10. When the intruders first arrived there were massive murders because there were more of us to kill then. They put bounties on the men, women and children. They have not stopped. They have no regard for our rights and feelings. All these people and their so-called government have no authority on turtle island. They need full true knowledge about the original people of onowarekeh. When anyone comes to our land we need to meet them upon their arrival to teach them the truth about turtle island and their duties to us.

In the beginning they sat with us in council. The kaianerekowa great peace was explained to them to learn and understand the existing laws of turtle island and the two row agreement which they agreed to abide by. Ownership of the land was not a concept of the indigenous people. They were given a choice to accept the kaianerekowa or return to where they came from, just like every country in the world today. When they saw the resources that existed here they decided to stay and start the extermination process to make money from exporting our resources, which continues today. The order to totally exterminate us was never rescinded in the entire Western Hemisphere. It is still the order. Their laws to murder us and steal all our possessions and resources are criminal acts in their imported legal system. If the intruders/benefitters don’t vote against these laws, then they too are perpetrators.

The late Mohawk singer, Robbie Robinson, sings about a call to kill the original people of onowarehke turtle island: “What law have I broken, What wrong have I done, That makes you want to bury me. . .

The general rode for sixteen days

The horses were thirsty and tired

On the trail of a renegade chief

One he’d come to admire

The soldiers hid behind the hills

That surrounded the village

And he rode down to warn the chief

They’d come to conquer and pillage

Lay down your arms

Lay down your spear

The chief’s eyes were sad

But showed no sign of fear

It is a good day to die (It is a good day to die)

Oh my children dry your eyes

It is a good day to die

And he spoke of the days before the white man came

With his guns and whisky

He told of a time long ago

Before what you call history

The general couldn’t believe his words

Nor the look on his face

But he knew these people would rather die

Then have to live in this disgrace

What law have I broken

What wrong have I done

That makes you want to bury me

Upon this trail of blood

It is a good day to die (It is a good day to die)

Oh my children don’t you cry

It is a good day to die

We cared for the land and the land cared for us

And that’s the way it’s always been

Never asked for more never asked too much

And now you tell me this is the end

I laid down my weapon

I laid down my bow

Now you want to drive me out

With no place left to go

It is a good day to die (It is a good day to die)

Oh my children don’t you cry

It is a good day to die (It is a good day to die)

And he turned to his people and said dry your eyes

We’ve been blessed and we are thankful

Raise your voices to the sky

It is a good day to die

Oh my children don’t you cry (don’t you cry)

Dry your eyes

Raise your voice up to the sky

It is a good day to die

https://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/DBG.CHAP2.HTM

mohawknationnews.com

kahentinetha2@protonmail.com

mohawkmothers.ca